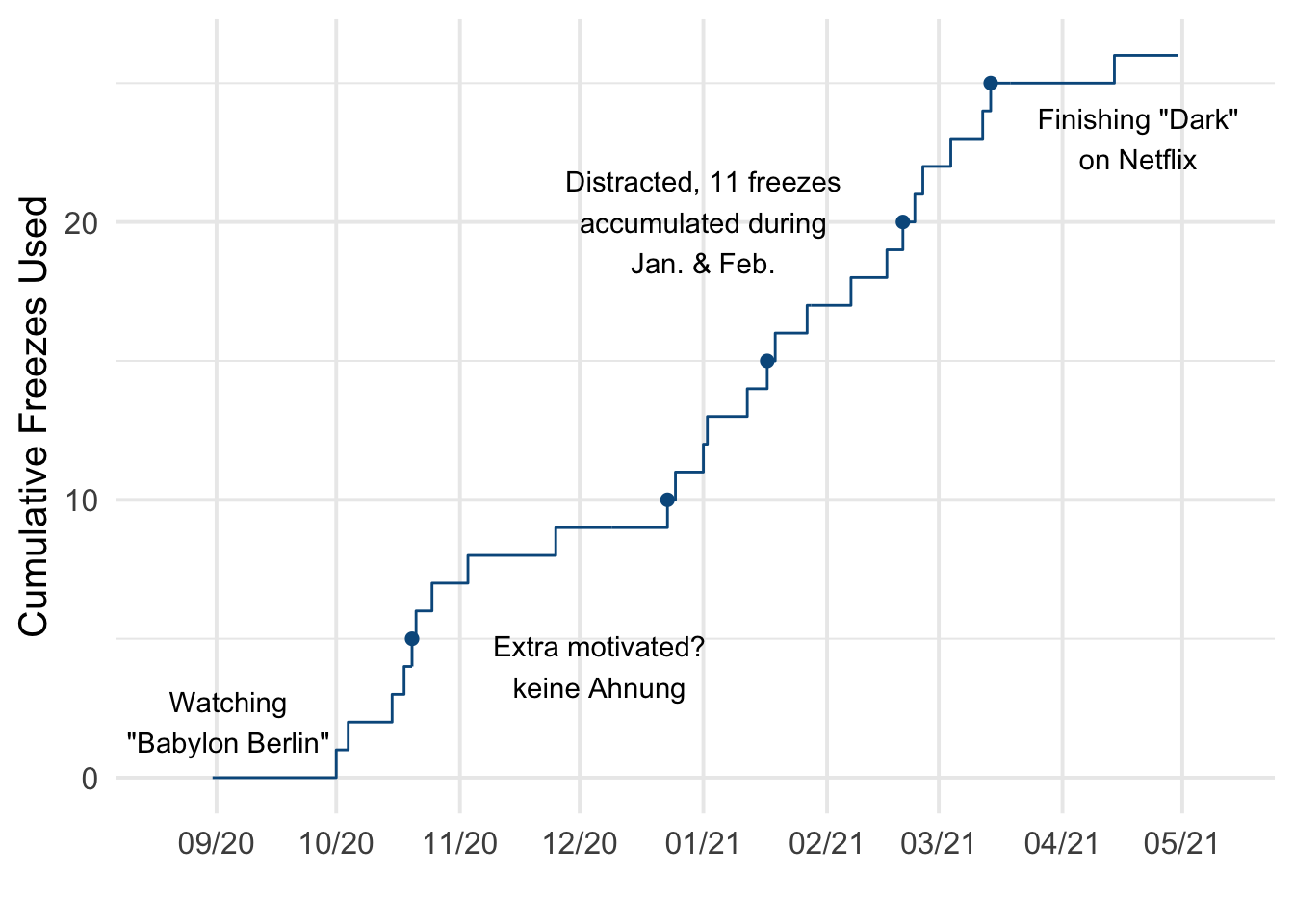

So, this is a small thing, but something I’m proud of. Over the past year, I’ve been practicing German (🇩🇪 Ich habe Deutsch gelernt!) using Duolingo’s mobile app. I don’t have an especially romantic reason for why I settled on the language, but I had watched the first season of Dark on Netflix in 2018, and don’t really enjoy dubbed foreign film/tv. Listening to the language prompted me to try a few lessons initially, but I settled into routine practice while finishing Babylon Berlin1 last fall. I don’t remember setting an explicit goal to reach a year of daily practice, but we’re coming up on that point. According to the app, I’ve been on a streak of 217 days! Leider habe ich nicht jeden Tag geübt. There were several days where I missed my usual 20-25 minutes of practice, but Duolingo lets you purchase “streak freezes” with in-app currency to preserve your progress. Here’s a snapshot of my streak(s) over the past 8 months.

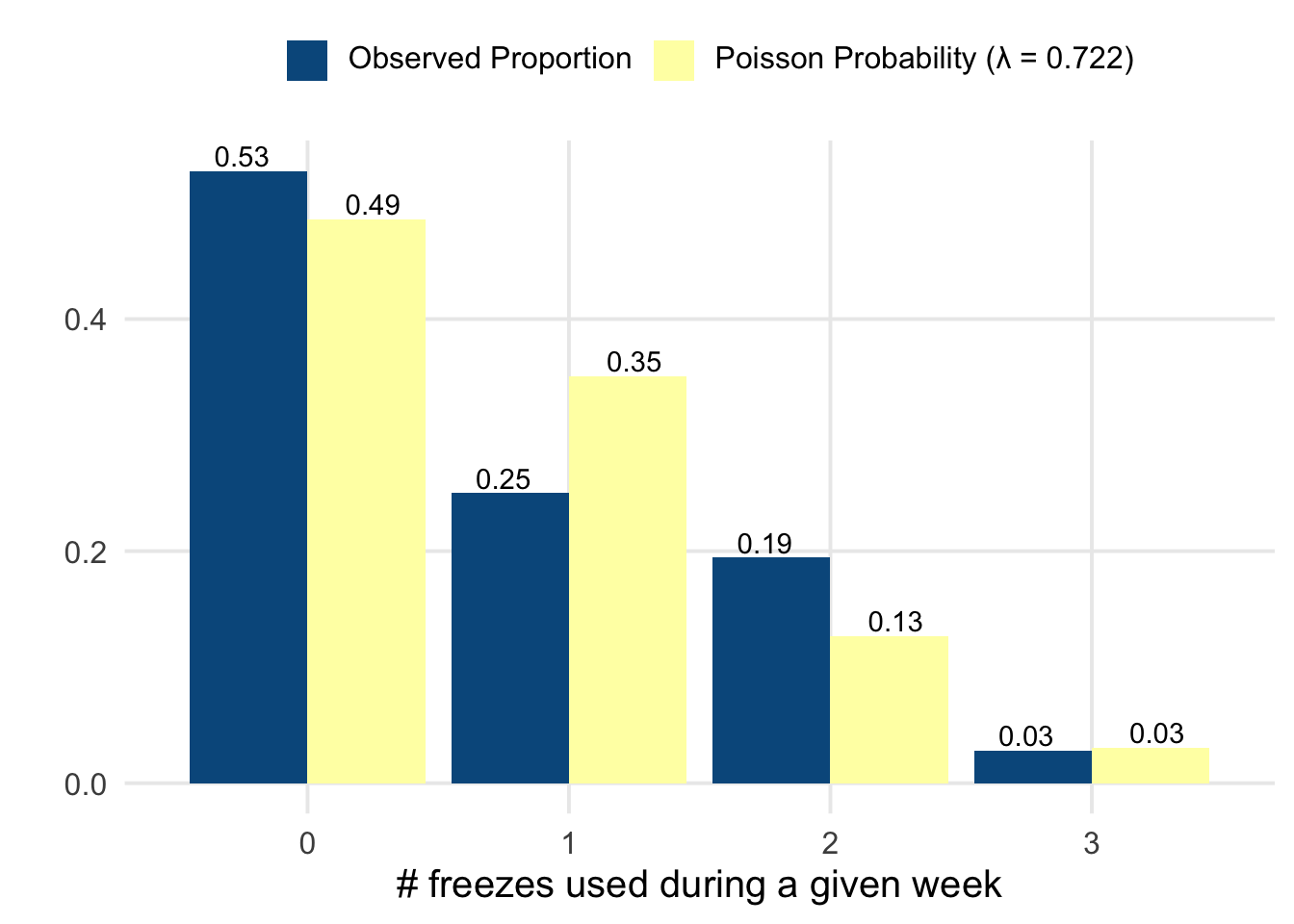

So, each freeze is a day that I’m “behind” on my goal. If I’ve used 26 freezes now, how many more should I expect over the next 4-ish months? I started right around the end of August, so 17 weeks from now would be close to my 1-year mark of daily practice. When counting the number of freezes on a weekly basis, the distribution looks fairly close to a Poisson distribution.

# I've omitted my prep code-- 'dates' is a dataset with 1 row/day,

# and an indicator 0/1 for whether a streak-freeze was used on a given day.

data.frame(dates)[1:3, ]## date freeze mon wk

## 1 2020-08-31 0 Aug '20 1

## 2 2020-09-01 0 Sep '20 1

## 3 2020-09-02 0 Sep '20 1weekly <- dates %>%

group_by(wk) %>%

tally(freeze)

weekly %>%

summarise(wk = max(wk), m = mean(n), v = var(n), min = min(n), max = max(n)) %>%

kable(col.names = c("# Weeks", "Mean", "Variance", "Min.", "Max."), digits = 3)| # Weeks | Mean | Variance | Min. | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 0.722 | 0.778 | 0 | 3 |

library(distributions3)

compare_w_poisson <- weekly %>%

count(n) %>%

mutate(p = nn / sum(nn), poi = pmf(Poisson(0.722), n)) %>%

pivot_longer(p:poi)

ggplot(compare_w_poisson, aes(x = n, y = value, fill = name)) +

geom_col(position = "dodge") +

geom_text(aes(label = round(value, 2)), position = position_dodge(1), vjust = -0.25) +

scico::scale_fill_scico_d(name = "", palette = "nuuk", labels = c("p" = "Observed Proportion", "poi" = "Poisson Probability (λ = 0.722)")) +

labs(x = "# freezes used during a given week", y = "") +

theme(legend.position = "top", legend.text = ggtext::element_markdown())

Maybe my data isn’t a perfect fit to a Poisson distribution with the same mean, but perhaps it’s close enough to serve as a model for what we can expect. So, to be specific, let’s let

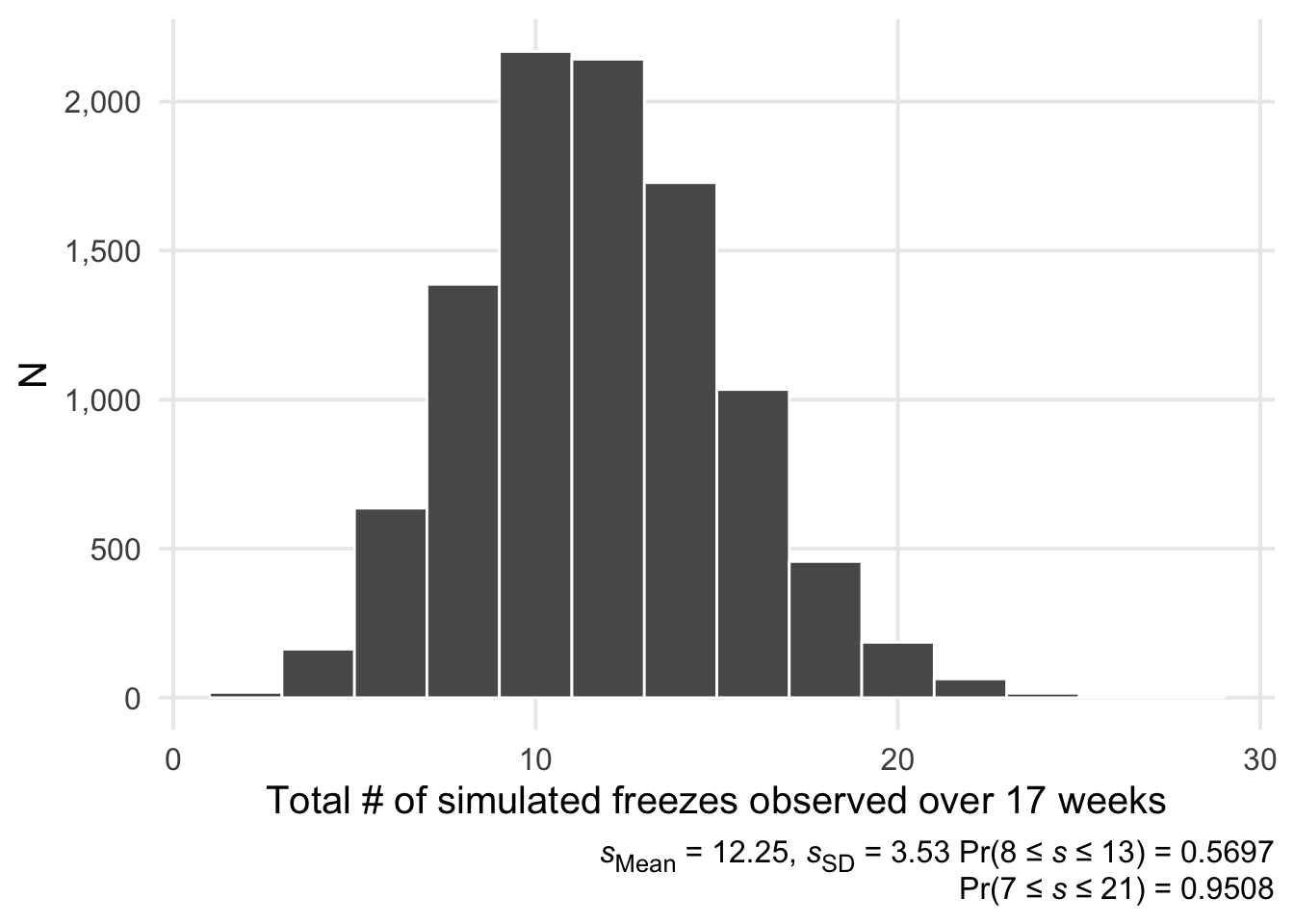

We can then simulate 17 weeks from \(X\) and sum the results, repeating this process say, 10,000 times. Or, more formally, we end up with a vector of sums \(\vec{s}\):

For this simulation, we’re assuming that the results of each week are independent of each other. This feels reasonable to me; autocorrelation in my tabulated weekly counts seems negligible.2 All that’s left is to set up a loop to collect the simulation results, and then we’ll use a histogram to visualize them.

X <- Poisson(0.722)

s <- c()

for (b in 1:10000) {

x <- random(X, n = 17)

s <- c(s, sum(x))

}

ggplot(tibble(s), aes(x = s)) +

geom_histogram(color = "white", bins = 15) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = scales::comma) +

theme(plot.caption = ggtext::element_markdown()) +

labs(

x = "Total # of simulated freezes observed over 17 weeks", y = "N",

caption = str_glue(

"*s*<sub>Mean</sub> = {round(mean(s), 2)}, *s*<sub>SD</sub> = {round(sd(s), 2)} ",

"Pr(8 ≤ *s* ≤ 13) = {sum(between(s, 8, 13)) / length(s)}<br>",

"Pr(7 ≤ *s* ≤ 21) = {sum(between(s, 7, 21)) / length(s)}"

)

)

We end up with a fairly normal-looking histogram, as would be expected by the central limit theorem.3 If the model is appropriate, it seems like I should expect between 8 to 13 additional freezes to be accumulated over this time period. The simulation results suggest there’s only a 22% chance that the number of freezes accumulated will be less than 10. Pulling everything together, by the end of August I’ll probably be between 34 and 39 streak-freezes deep. This means it’ll be at least a month after my starting point before I can truly claim I’ve met my goal. 😭

Which I recommend if you’re into noir, but the tragic & foreshadowed nature of the historical setting is captivating on its own. The soundtrack for each season has been excellent as well.↩︎

Using a lag of up to 15 weeks, the autocorrelations (assessed by

acf()) ranged between 0.15 to -0.25, but most were much smaller in terms of their absolute magnitude.↩︎update/edit: in the process of wrapping up this post, I came across this question/answer on SO, which suggests that my distribution here is actually Poisson, not normal. Theory would say we’re looking at a new Poisson distribution with \(\lambda = 0.722 \times 17 = 12.274\). The new \(\lambda\) is quite close to the sample mean from the simulation (the sample variance is a little off, but this is probably to be expected from the randomness of the simulation). I feel a bit silly about forgetting and then relearning about Poisson processes, but it was interesting to work through things.↩︎